A freshly minted graduate of a high school, college or technical school likely has no concept of mailing away for a product and waiting six to eight weeks for it. The irony in the battle to fill the skills gap is that the same people the materials handling industry hopes to attract are the most familiar with its optimal outcome: speedy, accurate delivery to the location of their choosing.

“E-fulfillment has changed the awareness of most consumers, because we want everything faster, and we want to know where and when and how it gets to us,” says Mitch Smith, vice president of engineering for Hytrol.

For those entering the industry, the breadth of available technologies can be daunting. Modern’s Basics Series is designed to familiarize beginners with concepts and solutions, but Tim Kraus, director of product management for Honeywell Intelligrated, has another idea.

“Get out and see as many automated systems as you can. YouTube and tradeshows are great, but nothing beats touring a facility with a guide who can tell you why decisions were made for various solutions,” Kraus says. “Facility tours are worth their weight in gold.”

The goal is to not get bogged down in details, Kraus says, which can happen to fledgling materials handling professionals eager to soak up as much information as possible.

“It’s easy to find training materials that dive deep into a cross-belt sorter and all the speeds and angles, but it’s harder to find the higher-level understanding,” Kraus says. “When does a cross-belt make sense compared to an automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS) or software solution? What is the purpose of the building, and how do you pick the right technology for the operation? It’s hard to find somebody who can do a good job giving that kind of tour.”

Amid the direct-to-consumer (D2C) revolution, even seasoned professionals might occasionally feel like they are starting from scratch.

“I was on a panel a few months ago that included a lot of experts in the parcel industry and warehousing and distribution,” recalls Brad Radcliffe, vice president of sales for sortation and distribution for Beumer Corp. “Driven by D2C and service levels, the last five years have been hectic as companies try to figure out what the next step is. Their customers want goods any time, anywhere, right now. For free.”

When asked whether the industry is in the beginning, middle or end of the D2C transformation, Radcliffe says every panelist agreed it’s just the beginning of the first phase of a five- to 10-year journey to transform supply chains. This article in Modern’s Basics Series reveals an industry in flux.

“We’re just at the beginning from an order fulfillment, technology, and labor model perspective,” Radcliffe says, “and nobody knows what the end result will be.”

From A to B to ERP

Conveyors are in many cases the primary and most cost-effective means of moving cartons, totes and packages. While conveyors themselves are fairly simple, Smith says, their ability to communicate with one another and related systems is becoming increasingly sophisticated.

“What is different and growing is the control capability and electronics on the conveyors that are relaying data to warehouse control systems, which in turn send information to higher-level systems to control every step along the way,” he says.

In DCs today, everything starts at the enterprise resource planning (ERP) or warehouse management system (WMS) level. Information is brought down to the warehouse control system (WCS), which then helps manage and direct the movement of products, equipment and people within the operation. For example, products in totes or cartons are routed to specific picking locations within a fulfillment center. Upon completion of that work, they are inducted back onto the conveyor and routed to the next locations. There’s a lot of software-based traffic management done to route that specific, discrete order to the right locations so it can be properly picked and fulfilled.

Once an order has reached all of its expected destinations, other functions might take place such as inserting an invoice, adding void fill, taping, sealing, labeling, in-motion weighing, manifesting and then sortation to the appropriate parcel carrier destination by zip code before it’s loaded onto a trailer or van.

“Along the way, lots of different interfaces are involved, and information is passed back and forth to the WCS, the ERP, and even back to the customer so they know their order has been picked and where it is each step of the way,” Smith says. “The mechanical piece is pretty cool and exciting, but so is the ability to connect these things. What that really means is software development, from the design of systems and electronics all the way to business intelligence and maintenance software. A lot of it is software-centric, which I would think would be exciting for most youngsters today.”

The maintenance aspect of connectivity and the Internet of Things is one of the more exciting recent developments, Smith adds. Written maintenance manuals for conveyors and equipment models have traditionally been the resource used for troubleshooting.

“That’s changing because some of the control systems and user interfaces can graphically see the conveyor system and its current state of operation,” Smith explains. “If there’s an error, the system can trigger codes and alerts to smart phones and create awareness of an issue immediately. Once a manager arrives, the system can present a list of troubleshooting steps. If the manager still cannot resolve it, a service department can remotely see the same detailed, real-time status and help them fix it. All those layers of interconnectivity and information are the wave of the future.”

For example, augmented reality on a smart device can overlay a repair tutorial onto the real-world component, or provide videos along with the voice of a support expert who can visually see what the customer is seeing while accessing relevant data.

Sorting it out

As products and customer orders continue to get smaller and smaller, DCs need to ship a lot of envelopes and handling thin, lightweight individual items, creating a sortation challenge.

“If it goes to the wrong lane, carrier and customer, you have lost money on that shipping process,” Smith says. “That means selecting the correct sortation method or technology. The more accurate, or the more destinations, generally the more expensive the equipment, so you need to make sure you’re spending dollars in the right place. The application should drive the sortation equipment. Product, accuracy and destinations are all factors to select the correct sorter for the job.”

Conveyor & Sortation Equipment

I. Hardware

A. Conveyor

1. Non-powered

a. Roller

b. Wheel

c. Chute

2. Powered

a. Transportation

(1) Belt

(2) Roller

(3) Modular belt

b. Accumulation

(1) Minimum pressure

(2) Zero pressure

(3) Non-contact

B. Sorters

1. Line sorters (e.g., sliding shoe)

2. Loop sorters (e.g., bomb bay, cross-belt, tilt tray, etc.)

II. Software

A. Equipment level control

1. Device level control (e.g., variable frequency drive)

2. Conveyor level control (e.g., zone controllers on accumulation conveyor)

3. Sub system level control (e.g., 5 to 1 conveyor merge and sorter)

B. Order processing control

1. Storage

2. Planning

3. Routing

4. Picking

5. Wave management

6. Labor management

What does it look like when done right?

1. Material flow – An ideal materials handling system is designed to accommodate fluctuations in activity throughout the day and business levels throughout the year.

2. Information flow – An ideal connected distribution center gets the right information to the right people at the right time.

a. Not too much information

b. Not the wrong information

c. Not to the wrong people

Radcliffe says D2C’s impact on functions like reverse logistics and crossdocking is driving further innovation in the capabilities of line and loop sortation systems. Traditionally, sorters were equipped with mechanical divert triggers that were committed to a specific item after it was scanned and inducted somewhere upstream.

“Those destinations then become inflexible physical limitations. To change them, you’d need a crew to move sensors, triggers and destinations, which takes time and money,” Radcliffe says. “Today, every single carriage carrying a product going around a loop talks to every one of those carriages so the system always knows its overall status. There’s no longer a huge array of physical sensors because communication can take place in real time. This is a huge time saver when you want to change the shape and location of a destination because the product changed. You can do it on the fly.”

Driven by larger SKU sets and smaller inventories, crossdocking is also growing tremendously, Radcliffe says, with some facilities processing one million cases per day from inbound pallets to outbound pallets bound

for stores or a regional distribution center (RDC) network.

“They’re cutting out billions in transportation costs by consolidating those truckloads, and crossdocking lends itself to loop sorters of all kinds, including tilt-trays and cross-belts,” he says. “It’s interesting for warehousing and distribution because they’ve never had to deal with those types of volumes.”

Cross-belts are suited to handling volumes of small product in a small footprint, whereas standard tilt-tray sorters can handle large 72-inch products. Another benefit of loop sorters, Radcliffe says, is their relatively easy expansion, including the ability to stack sorters two- or three-high without interrupting service levels.

Honeywell Intelligrated’s Kraus notes that cross-belt sorters shine in applications where there are 1,000 different orders at a time, consolidation into an e-commerce order, and multiple sort destinations.

Integrated sensors allow for dynamic adjustments to conveyor and sortation systems, while simplifying maintenance tasks.

“But again, get a high-level understanding of the options before you get into the details of each equipment type,” Kraus says. “Some types are very mature and have been around a long time and are widely used. Others are brand new, maybe more robotic type things. Before you can decide what makes sense for a project, get a basic understanding of automated solutions. What are their pros and cons, how mature are they, and how does that match up to the application?”

For those on the buying side, Kraus emphasizes an understanding that every requirement in a request for proposal (RFP) can have related trade-offs that a system integrator will need to account for. When shopping for a car, for example, more leg room, horsepower and trunk space can impact fuel efficiency and cost.

“If you want to state that a system must handle the biggest item you have, the integrator has to account for that and design around how a system can handle an item like a recliner,” Kraus explains. “That presents throughput, layout and operational considerations; bigger items mean a bigger system footprint and lower rate. New companies with younger engineering staffs don’t always realize those specifications would have such detriments to other parts of the business. Think through these things before you make rigid requirements.”

It is common for RFPs to aim for projected volume five years from now during a peak, Kraus says. For the system integrator to accommodate that volume may look very different than if they’re asked for a more scalable system that can meet expected peak in year three while planning for growth in the future.

“Instead of planning for five or seven years out, what if you shorten that to three and leave room for future additions?” Kraus says. “When you need expansion, you can then do it in a way that doesn’t require you to shut down the operation.”

For example, plan for where future destinations or divert lanes or operational areas might be. Or maybe the initial sort is by line or loop sorter, but is designed to add a secondary sort off the initial sort lane in year three. After items come off one sliding shoe divert, there are then four more diverts to quadruple the number of destinations. “If you think about that upfront,” Kraus says, “you’ll be much better set up for success.

Companies mentioned in this article

View Conveyors & Sortation Products and Accessories

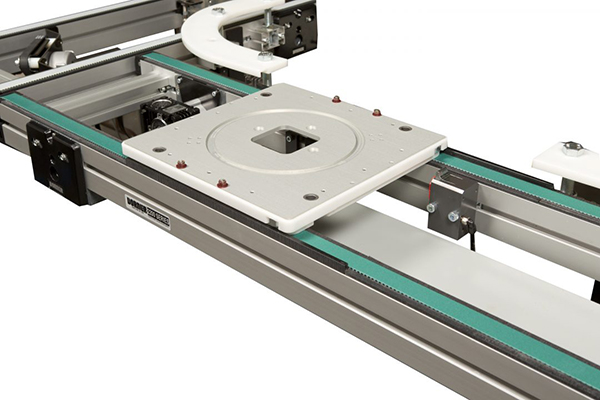

2200 series Precision Move Pallet System conveyor

2200 series Precision Move Pallet System conveyor

Conveyor moves pallets with precision in assembly automation processes.

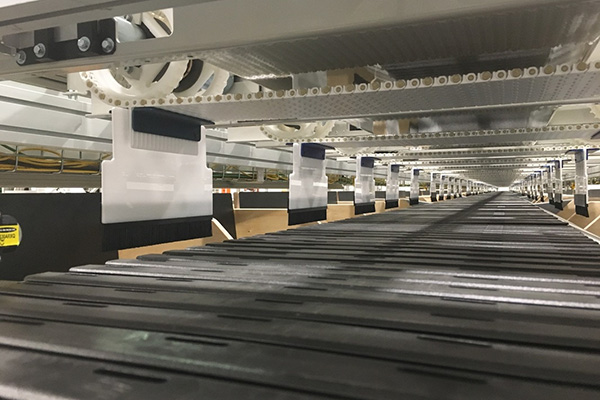

BG Sorter family

BG Sorter family

Sorter equipped with integrated, real-time wireless communications.

Sweeper Sorter high-speed unit sorter

Sweeper Sorter high-speed unit sorter

Sort polybags, small items at rates up to 7,200 units per hour.

Bulk Bag Weigh Batch Discharger

Bulk Bag Weigh Batch Discharger

Bulk-bag discharger conveying system.

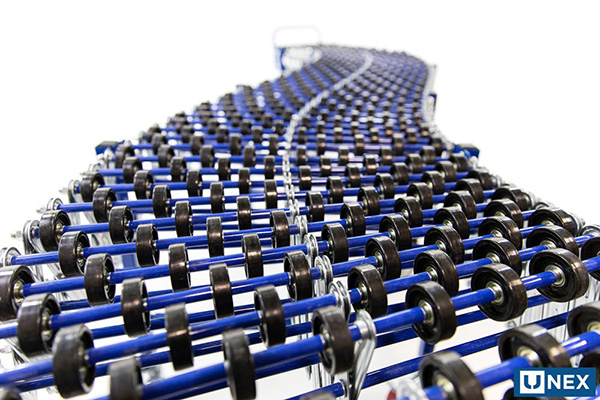

FWS Flex Wheel Series gravity conveyor

FWS Flex Wheel Series gravity conveyor

Flexible gravity conveyor can be used anywhere in a facility.

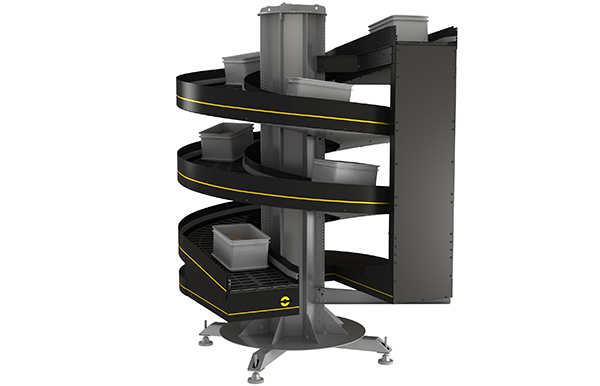

Spiral Lift

Spiral Lift

Vertically convey boxes, totes in multiple sizes with spiral lift.

Article topics